Legal Issues in Broken Trust

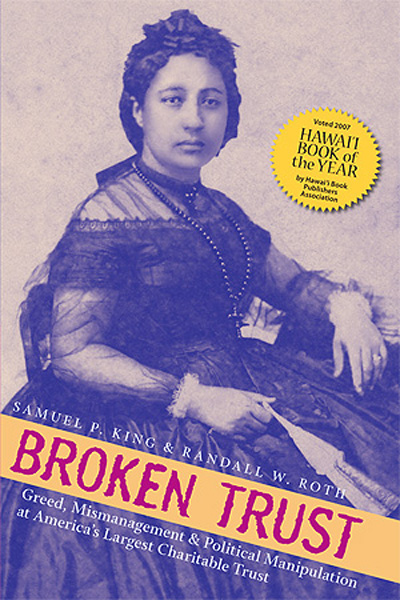

In 1884 Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, the last direct descendant of the Hawaiian monarch Kamehameha the Great, placed the bulk of her estate in charitable trust to establish and maintain “two schools, one for boys and one for girls, to be known as, and called the Kamehameha Schools.” The land holdings of what came to be known as the Bishop Estate are so large that they have been described by the New York Times as “a feudal empire so vast that it could never be assembled in the modern world.” For many years, however, Bishop Estate was “land-rich and cash-poor,” generating just enough income to keep both schools operating. When Hawaii became the 50th state and jet travel made the islands into an accessible destination, the princess’s trust quickly became the nation’s wealthiest charity, with an endowment that the Wall Street Journal described as larger than Harvard’s and Yale’s combined. In 1984 a United States Supreme Court decision forced the trustees to sell some estate land that many years earlier had been made available to homeowners on long-term leases. Suddenly Bishop Estate was cash-rich, too—a windfall that seemed to bring out the worst in Hawaii’s most powerful political leaders. A series of dramatic and often shocking events during the late 1990s shook the state’s conservative power structure to its foundations, snowballing into what 60 Minutes called “the biggest story in Hawaii since Pearl Harbor,” and The American Journalism Review described as “the kind of story that makes journalists salivate like hungry dogs.” Federal judge Samuel P. King and law professor Randall W. Roth have brought the story to life in their book, BROKEN TRUST: Greed, Mismanagement & Political Manipulation at America's Largest Charitable Trust. The following legal issues, presented alphabetically, form the core of this real-life drama.

ATTORNEY-CLIENT PRIVILEGE. While case law is mixed, most courts do not allow trustees to use the attorney-client privilege to withhold important information about trust administration from the beneficiaries of private trusts, or from the attorney general with respect to charitable trusts. Yet the probate court ruled that the Bishop trustees could use the privilege to withhold documents from Hawaii’s attorney general.

CO-INVESTMENT. Bishop trustees created a conflict of interests when they invested personal funds in private business deals in which they had also invested trust funds. One reason for the restriction on co-investing is that trustees will be tempted to consider their own interests when making subsequent decisions about the investment (i.e., that they will throw good money after bad for the impermissible purpose of salvaging their own private investment). Bishop Estate trustees apparently did exactly that.

COMMUNITY INTERESTS. Were the Bishop Estate trustees required to invest to produce the highest possible returns or could they take into account other factors, such as the impact their investment polices would have on the community? The answer is not completely free from doubt. In another significant case, the trustees of the Hershey trust voted in 2002 to sell stock in the Hershey Foods Corporation for upwards of $15 billion. This would have enabled the trustees to diversify trust investments and increase dramatically the money available to pursue that trust’s educational mission. The Pennsylvania attorney general and court refused to agree, however, in large part because of opposition from community leaders who feared that the new owner would move company headquarters and operations out of the state. Also in 2002 the new Bishop Estate trustees gave in to public pressure and withdrew from a legal battle over the trust’s right to divert mountain stream water for land-development purposes. Although this decision arguably hurt the trustees’ ability to educate as many children as possible, Hawaii’s attorney general and a court-appointed master chose not to oppose the trustees’ popular decision.

CONFIDENTIALITY. Fiduciaries are sometimes subject to a duty of confidentiality. Bishop Estate trustee Lindsey claimed that trustee Stender had such a duty and then violated it when he told friends, and eventually reporters, about what went on at trustee meetings. Stender claimed that Lindsey violated a duty of confidentiality when she released to the media her “confidential” report on the quality of education at Kamehameha Schools.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS. Trustees must avoid conflicts of interest and they must take appropriate action when a conflict cannot be avoided completely. A Hawaii statute additionally requires that trustees seek court instructions when there is a significant conflict of interest. Bishop Estate trustees often did not do this; instead, they devised their own ways of dealing with conflicts, sometimes with astonishing results. Trustee Peters “recused” himself as a Bishop Estate trustee just long enough to negotiate for the purchase of Bishop Estate land on behalf of the buyer!

COOPERATION. Co-trustees are required to work together in the best interests of the trust. A court may remove a co-trustee if he or she lacks the ability or willingness to do so. Bishop Estate trustees sometimes refused to share important trust information with each other (a clear breach of their fiduciary duty), and their working relationships became strained to a point approaching physical violence on several occasions.

CORPORATE FORM. Would it make good sense in today’s world to structure a multi-billion-dollar organization with thousands of employees like Bishop Estate as a multi-trusteed trust? Broken Trust author Judge King suggests that it is time to convert Mrs. Bishop’s trust into a not-for-profit corporation. As envisioned by King, instead of five highly paid trustees who tend to micromanage, there would be a larger number of unpaid directors who would limit themselves to setting policy and providing oversight to a well-paid chief executive and highly qualified staff. Because unpaid directors of not-for-profit corporations have far less legal exposure than do trustees of a trust (by statute in most states), millions of dollars could be saved on liability-insurance premiums. Also, the organization’s charitable mission could evolve more easily with changing times. For example, a not-for-profit board of directors could legitimately decide to use existing resources to promote Hawaiian culture, conserve non-income-producing land, grant scholarships to other schools, and expand the organization’s outreach programs, all without first having to establish that the charitable purpose in the will (the maintenance of two schools) is illegal, impossible, impracticable, or wasteful.

CURRENT VALUES. If trustees do not provide accountings that are both accurate and complete, beneficiaries cannot evaluate trust performance. Bishop Estate trustees rendered annual accountings but steadfastly refused to disclose the current value of their vast land holdings and substantial business ventures, claiming that they had no idea what these assets were worth and that there was no need to know. Especially given the movement toward total-return investing, trustees should determine the current value of investment property at least annually, with hard-to-value assets estimated regularly and given periodic independent appraisal.

CY PRES. Traditionally, a trust’s charitable mission, even one that is no longer in tune with the modern world, can be changed only by showing that unforeseen circumstances have made the original mission illegal, impossible, impracticable, or wasteful. The standard is less stringent when the change would affect only an administrative provision (one that is a means to an end as opposed to the end itself). Bishop Estate trustees and Hawaii’s probate court sometimes acted as if this rule does not exist. For example, although Mrs. Bishop’s will directs the trustees simply to establish and maintain two schools, “one for boys and one for girls,” the two schools are now combined. Furthermore, the trust also functions somewhat like a land conservancy, providing culturally and environmentally sensitive stewardship for more than 350,000 acres of non-income-producing land. This is surely a laudatory endeavor, but Mrs. Bishop’s will says nothing about preserving or protecting the environment or Hawaiian culture.

DELEGATION. Except as otherwise provided by the terms of the trust, each trustee has a duty and the right to participate in trust administration. Trustees can delegate functions to a co-trustee only so long as each trustee continues to be responsible for, and exercises supervision and review of, all activities. Despite this rule, the five trustees of Bishop Estate utilized a “lead-trustee” system in which each trustee functioned like a chief executive for a different aspect of the trust’s activities, and individual trustees then made important decisions without first consulting with the others. For example, trustee Lindsey ran “education,” trustee Wong was in charge of “government relations,” and trustee Peters headed up “asset management.”

DILIGENCE. Trustees have a duty to stay informed about important trust matters. Trustee Stender reportedly stopped attending trustee meetings because he considered the chaotic, hostile sessions to be a waste of time and an insult to Mrs. Bishop’s memory. He also felt that he could not influence the outcome of any important issue (because the other trustees ignored or ridiculed what he said, and usually voted against him as a bloc). Even so, it was arguably a serious breach of trust for Stender to stop attending meetings.

DISCRIMINATION. Mrs. Bishop’s will does not limit school admission to native Hawaiians, but it does authorize the trustees to set the admissions policy and to use a portion of each year’s income for “support and education of orphans, and others in indigent circumstances, giving the preference to Hawaiians of pure or part aboriginal blood.” With minor exceptions, Bishop Estate trustees have always reserved admission to Kamehameha Schools for children who have Hawaiian blood. Some critics argue that applicants with a high quantum of Hawaiian blood should gain admission over those with lower levels, regardless of academic ability. Others maintain that any child, regardless of race, who has been informally adopted by a Hawaiian (a cultural practice known as hanai), should be eligible to attend Kamehameha Schools. And then there are those who argue that “Hawaiianness” should be based on culture and interests, not blood quantum or informal membership in a Hawaiian family. A non-Hawaiian applicant, rejected by Kamehameha Schools in 2002, is now challenging the Hawaiians-only admissions policy in court, arguing that it violates a nineteenth-century civil-rights statute. The IRS district office decided in 1999 to revoke Bishop’s Estate tax-exempt status because of its admissions policy, but the national office reversed that decision. Since then, to reduce the risk of a 14th Amendment challenge, the trustees have rejected government aid.

DIVERSIFICATION. It has been said that the three most important principles for prudent investing are “diversification, diversification, and diversification,” yet the Bishop Estate trustees retained most of the original estate, which was virtually all unimproved land. Depending on other factors, this could conceivably be prudent, and therefore acceptable under trust law, but the Bishop trustees’ additions to the trust’s already extensive land holdings are virtually impossible to justify under the prudent investor standard.

DUE DILIGENCE. Trustees are not permitted to make uninformed investment decisions. They must perform appropriate due diligence. Bishop Estate trustees sometimes skipped that step or appeared not to take it seriously. Examples discussed in Broken Trust include the purchases of Hamakua land, KDP Technologies stock, EMG services, and the Van Dyke Hawaiiana collection.

DUTY TO PROTECT. Co-trustees have a duty to use reasonable care to prevent a co-trustee from committing a breach of trust and, if a breach of trust occurs, to obtain redress. Trustee Stender knew of serious breaches and tried for years to get the probate court or attorney general to take action against the other Bishop trustees. When they declined to do so, he considered filing a lawsuit, but lawyers told him it would cost at least $2 million (which would have to come out of his own pocket), and that he would probably lose (because of a perceived connection between his co-trustees and the state judiciary). Despite Stender’s good-faith efforts to get others to do their job of policing the trust, he was later faulted for not filing suit against the other trustees.

FIDUCIARY DUTIES. When individuals agree to serve as trustees—which they cannot be forced to do—they automatically become subject to strict fiduciary duties, regardless of their understanding of those duties. It is not clear that the Bishop Estate trustees ever understood or even attempted to understand what was expected of them under trust law. When trustee Stender arranged for a workshop on fiduciary duties the other trustees refused to attend.

FLAWED ACCOUNTABILITY. Courts usually hold fiduciaries to high and unbending standards. Bishop Estate was an exception. According to the IRS and several court-appointed masters, the trustees treated Mrs. Bishop’s estate like “a personal investment club” and committed egregious breaches of trust, yet the Hawaii probate court allowed them to resign without paying any surcharges, damages, or reimbursement to the trust—they were not even required to admit they had done anything wrong! This outcome may be unique; it would be foolhardy for a trustee to expect comparable treatment after abusing any other charitable trust to the same extent.

IMPARTIALITY. Trustees are required to know whether the circumstances of any particular trust require them primarily to stabilize current returns, maintain the trust estate’s real value, or something else. Although Kamehameha Schools was admitting only a small fraction of applicants, for many years Bishop Estate trustees invested primarily for growth and secretly accumulated substantial amounts of income. Annual expenditures on Kamehameha Schools fell below 1% of the estimated value of the trust estate, an exceptionally low percentage. The estate grew in real dollars, but the IRS nearly revoked the trust’s tax-exempt status because the trustees had shortchanged the current generation of intended beneficiaries. Similar trustee behavior would breach the duty of impartiality in some private trusts.

INTERIM REMOVAL. Faced with compelling evidence of serious, ongoing breaches of trust, most courts immediately remove trustees temporarily so the trust’s interests can be protected until such time as the question of permanent removal can be decided. Hawaii’s probate court acted differently. Despite reports submitted by a court-appointed master and court-appointed fact-finder that listed numerous serious, ongoing breaches of trust, the probate judge declined to take definitive action until the IRS made its presence felt, nearly two years after publication of the “Broken Trust” essay. When the judge finally scheduled an interim-removal hearing, the trustee who had attempted suicide requested and received a postponement so he could recuperate fully before having to protect his individual interests. Meanwhile, he continued to collect nearly $100,000 each month in trustee fees despite his admittedly diminished condition. The probate court appeared to be more concerned about his due-process rights than the interests of the trust.

INTERMEDIATE SANCTIONS. For many years, when the IRS discovered abuse involving a charity, it had the choice of revoking the organization’s tax-exempt status (which would hurt the charity’s intended beneficiaries), or doing nothing (which hardly seemed appropriate). Congress’s enactment of the Intermediate Sanctions law in 1996 changed that. The new law gave the IRS the authority to level substantial sanctions directly against the insiders who had taken improper advantage of their control over the charity. Bishop Estate trustees spent nearly $1 million lobbying against the bill. Because the bill posed a threat only to them (and could only benefit the trust’s beneficiaries) the trustees’ lobbying would have been a conflict of interests breach of trust, even if they had used their own money. They used trust funds, which compounded the offense.

IRS ROLE. Historically, the IRS has played a limited role in regulating charities, deferring almost completely to the local attorney generals. But the slow-moving Bishop Estate controversy reached a sudden climax suddenly when the IRS refused to communicate with the sitting trustees and threatened to revoke the trust’s tax exemption if a list of nonnegotiable demands were not met. As a practical matter, that virtually forced the probate court to remove the trustees and reform the trust. Was it proper for the IRS to assume such an active role? Opinions vary greatly.

LAWYER’S DUTY TO REPORT. Hawaii has a probate rule that requires trust counsel to report a trustee’s serious misconduct to the beneficiaries or, in the case of a charitable trust, to the probate court (after first attempting to get the trustee to correct the problem). Depending on the circumstances of each situation, including the jurisdiction in which it occurs, a lawyer may be required to disclose a trustee’s serious misconduct (as was the case under Hawaii law), prohibited from disclosing such misconduct (as used to be the rule in most states), or permitted to disclose it (as is the trend).

MANDATORY AND PRECATORY LANGUAGE. Mrs. Bishop used mandatory and precatory language in different sections of her will. For example, she directed that her trustees expend annual income on the schools, publish accountings in a Honolulu newspaper, and hire only Protestants to teach at Kamehameha Schools. By comparison, she only desired that the trustees provide education in the common English branches, and that instruction in the higher branches be subsidiary. In some places, she directed that her trustees “have the power” to do something. Despite the presence of a mandatory word such as “direct,” such provisions merely give trustees discretion to use the power in question. Bishop Estate trustees frequently referred to Mrs. Bishop’s will as “sacred,” yet regularly deviated from not just the precatory provisions, but mandatory ones as well.

OBEDIENCE. Although trustees generally must follow any mandatory language in the governing document, Bishop Estate trustees often failed to do so. For example, they did not expend all trust income on the trust’s charitable purpose nor did they publish annual accountings in a Honolulu newspaper. Of the trustees’ many breaches of trust, these were the most easily provable.

OVERSIGHT. Effective oversight is never certain. Each individual Bishop Estate trustee had a duty to monitor the actions of the other four and to take appropriate action when serious breaches of trust became evident. The Hawaii attorney general also had oversight responsibility, as did the probate court and the master the court appointed each year to review the trustees’ accounts. Furthermore, trust counsel were supposed to report serious trustee misconduct to the probate court, and Supreme Court justices arguably had on-going responsibility (i.e., the power to “hire” arguably included the power to “fire,” along with a responsibility to monitor trustee performance). Despite all this, obvious breaches of trust went unchecked for years.

PARENS PATRIAE. Beneficiaries of non-charitable (private) trusts have legal standing to sue the trustees of their trusts. That enables beneficiaries to hold trustees accountable. But charitable trusts technically lack beneficiaries other than the public-at-large. Rather than allow any member of the public to sue trustees of charitable trusts, trust law bestows upon the attorney general of each state both the power and the responsibility to represent the intended beneficiaries of every charitable trust (i.e., to act as their lawyer). This concept, called parens patriae, has been a part of the common law for centuries. Prior to publication of the “Broken Trust” essay, however, a series of attorneys general in Hawaii had decided not to take action against Bishop trustees, even when trustee Stender repeatedly requested that they do so. Later, Stender sued the State, claiming that he had been damaged personally by the failure of the attorneys general to do their job properly. Stender eventually dismissed this lawsuit as a condition of entering into a global settlement that abruptly ended all investigations into wrongdoing at Bishop Estate.

PERSONAL COUNSEL. When trustees retain lawyers to assist them in carrying out their fiduciary duties, it is appropriate that trust funds be used to pay the fees. Such lawyers are sometimes called trust counsel. When trustees retain personal counsel to watch out for the trustees’ personal interests, the propriety of using trust funds is less clear. In such situations it is prudent and may be required that the trustees petition the court for instructions. Bishop Estate trustees regularly used trust funds to pay attorneys who in some cases appeared to be representing the personal interests of individual trustees. A court-appointed master concluded that the trustees should have sought probate court instructions before using trust funds to pay those lawyers. He also faulted the lawyers for not questioning the trustees’ use of trust funds to pay for services that arguably furthered the trustees’ personal interests over those of the trust.

POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT. Tax-exempt organizations are not supposed to involve themselves in political campaigns, yet Bishop trustees systematically raised money for politicians and assisted in a variety of other ways. They also paid substantial consulting fees, retainers, and salaries to key government officials. The head of Hawaii’s senate money committee, for example, was on the trust’s full-time payroll and was given a credit card that he used in casinos and strip clubs. Bishop Estate also paid his legal expenses when he was under federal investigation for public corruption.

PRUDENT INVESTING. Prudent investing generally requires an overall plan, due diligence, and regular monitoring of existing investments. Bishop Estate trustees reportedly made ad hoc investment decisions based on personal relationships, and without proper due diligence. For example, when Robert Rubin left Goldman Sachs to join the Clinton administration, he sold his partnership interest back to Goldman Sachs for its promissory note, and then asked Bishop Estate to guarantee that note—which was reportedly in the vicinity of $50 million. Although the charity did not have the expertise needed to ascertain the trust’s exposure and determine an appropriate price, the trustees quickly said “yes.” They also invested tens of millions of dollars in complicated oil and gas exploration deals that individual trustees had trouble explaining during the depositions taken when they later sued the promoter.

PUBLIC CHARITY. When Mrs. Bishop wrote her will, Hawaii was an independent nation with its own tax laws. Now, however, the trust is subject to the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. Because Bishop Estate has a single benefactress, some people assume it is a private operating foundation (like the Queen Liliuokalani Trust). Bishop Estate, however, is a public charity because its charitable purpose is to operate a school (defined in the tax code as “an educational organization that normally maintains a regular faculty and curriculum and normally has a regularly enrolled body of pupils or students in attendance at the place where its educational activities are regularly carried on”). It is unclear to what extent the trustees can pursue other charitable purposes (e.g., outreach programs and land conservancy activities) before the trust is no longer classified as a school, and therefore becomes a private operating foundation, for tax purposes.

PUBLIC POLICY. Public policy arguably should prevent trustees from entering into private contracts that limit the ability of successor trustees to hold them accountable for harm done to the trust, yet Bishop Estate trustees managed to do exactly that. The successor trustees chose not to seek accountability from their “ousted” predecessors because of an “insured vs. insured” provision in several large liability insurance policies their predecessors had purchased with trust funds. The new trustees’ lawyers—who included lawyers who had represented the former trustees—reportedly advised against seeking accountability or even cooperating with the attorney general’s office in its effort to hold the former trustees accountable, saying that it would jeopardize $75 million of insurance coverage (under the “insured vs. insured” provision). The new trustees, also concerned about the personal strain and financial cost of pursuing the former trustees and the former trustees’ lawyers, chose not to seek a declaratory judgment on the public-policy issue.

REASONABLE COMPENSATION. Trustees are not allowed to pay themselves fees in excess of what their services are worth to the trust. Bishop Estate trustees used a statutory formula to calculate their fees, and then, with of goal of establishing reasonableness, compared those amounts to compensation being paid to chief executives of other multi-billion-dollar organizations. The IRS imposed sanctions anyway, because use of a statutory formula does not necessarily establish reasonableness for tax purposes and amounts paid to chief executives of for-profit enterprises are of limited value when setting compensation for trustees and directors of charities.

RELIANCE ON OTHERS. Trustees should not seek legal advice from lawyers with a conflict of interests, nor should they put someone who has a conflict of interests in control of the flow of information within the organization. Yet when interim trustees replaced the ousted Bishop Estate trustees, they chose as their chief executive the person who had served for the past decade as the former trustees’ top in-house lawyer. The interim trustees also sought legal advice from outside counsel who had advised the former trustees.

RELIGION. In her will, Mrs. Bishop directed that trustees of her trust and teachers at Kamehameha Schools always be members of the Protestant religion. In the 1960s, a court determined that the requirement that teachers always be Protestant did not violate anti-discrimination labor laws because the school was a private, religious school. In 1994, however, the 9th Circuit ruled that the Protestants-only hiring mandate violated the law because the school had evolved into a secular institution. When selecting trustees, state Supreme Court justices claimed for years to be following the letter of the will, if not its spirit (appointing, among others, a lifelong Catholic who supposedly “converted” to Protestantism on the eve of his selection and a practicing Mormon who had received Protestant baptism as an infant). Currently the probate judge selects trustees, and judges cannot take religion into account when making such decisions. In short, Mrs. Bishop’s instructions regarding religion are no longer honored.

SECRECY. Although trustees generally have a duty to keep beneficiaries informed about the trust, Bishop trustees were notorious for providing inadequate information in their annual accountings. For example, they routinely used wholly owned corporations to conduct business, but they did not provide consolidated financial statements or crucial details about the corporations. Tax-exempt charitable organizations should operate relatively openly, and Mrs. Bishop directed her trustees to publish an accounting each year in a Honolulu newspaper. Despite this instruction, trustees operated in extreme secrecy for many years, insisting upon and enforcing confidentiality agreements from trust employees. When the president of the Bishop trust’s wholly owned insurance company told the outside auditor about serious wrongdoing, the trustees fired him and immediately secured a court order effectively preventing him from turning over evidence of trustee misconduct to the attorney general or to the media. This penchant for confidentiality (and the courts’ willingness to support it) continued even after five trustees resigned under fire in 1999: the new trustees encouraged the probate judge to seal documents that had been part of the official record. Then, when the new trustees abruptly fired their chief executive for alleged illegal behavior, none of the parties would comment on the $400,000 settlement they reached with him. It, too, was deemed “confidential,” although such a settlement is somewhat troubling in the context of a charitable organization.

SELECTING TRUSTEES. Mrs. Bishop directed that justices of the Supreme Court of the Kingdom of Hawaii select successor Bishop Estate trustees. Because justices at that time had original jurisdiction over probate matters, they would have selected successor trustees as part of their official duties, even if the will had been silent about trustee selection. When Hawaii became first a republic, then a territory, and then a state, the Supreme Court ceased to have original jurisdiction over probate matters, but the justices continued to select Bishop Estate trustees, now in an unofficial “individual capacity.” Although no one can be forced to select trustees, when the justices agreed to do so, they assumed a duty to perform the selection with due care and the goal of benefiting the trust. It was never clear whether judicial immunity would apply in the event that someone sued the justices for negligence (or worse) in selecting trustees.

SIMULTANEOUS INVESTIGATIONS. The attorney general simultaneously directed civil and criminal investigations of the Bishop Estate trustees. She instructed members of the criminal team not to communicate about the case with members of the civil team, and vice versa. Although civil and criminal teams shared the same office, the attorney general contended that a “conceptual wall” had been erected. The criminal team eventually secured a series of grand jury indictments, but all were thrown out on procedural grounds and a panel of substitute Supreme Court justices ruled that there had been prosecutorial misconduct. The misconduct was unrelated to the civil investigation, but some observers concluded that the attorney general had put herself in a difficult legal position by trying to conduct simultaneous investigations. The trustees argued that her “wall” was more like a “chain-link fence” (i.e., that she had used the criminal investigation to gain leverage on the civil side, and the civil investigation to obtain evidence that she could not have gotten on the criminal side of the “wall”).

SPLIT-PERSONALITY TRUST. To be a charity and enjoy tax-exempt status, an organization must be formed and operated to serve a public benefit. By contrast, businesses primarily seek profits. The culture at a typical charity is noticeably different than the culture at a typical business. Because Bishop Estate trustees engage extensively in business activities (directly or through profit-seeking “subsidiaries”) while simultaneously operating a public charity, many people view the trust as two separate organizations with two separate cultures: a business, Bishop Estate, and a charity, Kamehameha Schools. A succession of trade names suggests an evolution of self-identity: what for many years was officially known as Bishop Estate eventually became Bishop Estate/Kamehameha Schools, then Kamehameha Schools/Bishop Estate, and finally Kamehameha Schools. Some observers call this frequent rebranding window dressing, and contend that the trustees need to become a true charity with only passive-investment assets in its endowment. They further contend that the trust’s split personality as part business/part charity renders it less effective than it otherwise could be as either a business or a charity.

STANDING. There is a national trend toward granting legal standing to a group with a special interest in a charitable trust when the state attorney general chooses not to take action despite indications of serious abuse. When it became clear that the system of oversight in Hawaii had broken down and that no one with legal standing was taking steps to hold the Bishop Estate trustees accountable, a group of Kamehameha Schools alumni, parents, students, and teachers asked for standing. Hawaii’s attorney general joined with the Bishop Estate trustees in successfully opposing those efforts.

TAX-EXEMPT STATUS. Change came quickly to Bishop Estate after the IRS threatened to revoke the trust’s tax-exempt status. The threat was real. The sitting trustees had apparently violated every condition of IRC section 501(c)(3) status: private inurement (excessive compensation and inappropriate side benefits), private benefit (sweetheart deals for friends and relatives), commerciality (overemphasis on the business side of trust activities), failure to pursue the charitable mission (less than 1% of estimated value expended on Kamehameha Schools each year), involvement in political campaigns (illegal financial assistance to, and direct involvement in, the campaigns of favored candidates), and self-serving lobbying activities (more than a million dollars of trust funds secretly spent lobbying against federal and state legislation that would limit how much the trustees could pay themselves in compensation). There were also major problems with the trustees’ annual accountings, administration of the school, and management of the trust estate.

TRUST COUNSEL. Lawyers should always know who is, and who isn’t, a client. Some of the lawyers in the Bishop Estate controversy said they were representing “the trust” and took orders from the three-trustee majority faction. Yet trusts are traditionally viewed as relationships between trustees and beneficiaries, not as separate entities. The trustees own the assets, hire the employees, pay the bills, and retain counsel. Hawaii’s probate court eventually determined that trust counsel for Bishop Estate actually had five clients, not one, and the five were at odds with each other. This created confusion over the lawyers’ conflicting duties. They could have addressed the potential for such conflicts in an engagement letter (as experienced estate planners do when representing a married couple).

TRUSTEE SELECTION. Settlors should give serious consideration to the best way to select future trustees, especially if they expect the trust to last many years into the future. Mrs. Bishop directed that Supreme Court justices select all her future trustees. At the time, Hawaii was an independent nation. More than a century later, state Supreme Court justices were still selecting trustees, supposedly in their non-official capacity as ordinary citizens (because their court had only appellate jurisdiction over probate matters). By the 1990s, critics felt the justices were selecting trustees on the basis of political payback, with no apparent concern for the trust’s intended beneficiaries. A few months after publication of the Broken Trust essay, the justices stopped selecting trustees, citing a “climate of public cynicism.” Currently the probate judge chooses all Bishop Estate trustees. Hawaii’s last monarch, Queen Liliuokalani, chose a different trustee selection process for the charitable trust she created; she empowered her trustees to select their own successors. While one can easily envision problems with a self-perpetuating board, that approach has worked well for the Queen Liliuokalani Trust. As for the Bishop Estate, critics question whether a single probate judge can reasonably be expected to withstand the intense political pressures that appear to have influenced the actions of five Supreme Court justices.

UNDIVIDED LOYALTY. Trustees must act at all times solely in the beneficiaries’ best interests, and in so doing, they must meet an unusually high standard of care and conduct. The duty of undivided loyalty includes an absolute prohibition against self-dealing—which Bishop trustees breached when they refused to step aside in the face of an IRS demand to do so in order to save the trust’s tax-exempt status. The trustees called this requirement “extortion.” It is easy to see how such a threat could be used maliciously, but whether it was fair to the trustees did not matter. The threat to the trust was real, and so the trustees were duty-bound to step down.

UNITRUST. According to the will, as interpreted by the Hawaii Supreme Court, the trustees were supposed to expend trust income annually. This arguably meant that they had a duty to invest assets in such a way as to generate a reasonable amount of annual income to expend on Kamehameha Schools. Yet for years the trustees invested primarily for growth rather than income. They also secretly accumulated over $350 million of income in defiance of the will. At the insistence of the IRS, the trust is now a “unitrust,” expending between 2.5% and 6% of the endowment each year pursuing the charitable mission, with a target-spending rate of 4%. For this purpose, the endowment does not include the non-income-producing trust land, worth billions in the current market.

UNPRODUCTIVE ASSETS. Trustees have a duty to make the trust estate productive. Bishop Estate trustees, however, own more than 350,000 acres of non-income-producing land (including 63 miles of valuable shoreline), worth billions of dollars. They do not list these parcels of land as investments; instead, they call them “program assets” that are being held indefinitely “for educational purposes.” Bernice Pauahi Bishop expressed a desire that the trustees not sell her land “unless in their opinion a sale may be necessary for the establishment or maintenance of said schools, or for the best for the best interests of my estate.” Critics contend that the trustees should sell the land so they can educate more Hawaiian children, and that the trustees have a duty to do so.

WAIVER OF ATTORNEY-CLIENT PRIVILEGE. The Hawaii Supreme Court threw out criminal indictments against the former Bishop Estate trustees after ruling that grand-jury testimony had violated the attorney-client privilege. The new trustees had waived the privilege for this limited purpose, but the justices said the question of who could waive the privilege (the former or current trustees) was an unresolved question in Hawaii that was best left for another day. Cases in other jurisdictions are mixed. In the Bishop Estate case, the justices’ ruling assumed, without so stating, that only the former trustees could waive the privilege.

WASTE. A court-appointed master concluded that the former Bishop Estate trustees had wasted trust funds on lawyers who actually represented the trustees’ personal interests rather than those of the trust. The master recommended that the successor trustees seek disgorgement of millions of dollars in fees already paid to certain lawyers. Instead, the successor trustees sought a “second opinion” from a law firm that advised the successor trustees not to attempt to recover any of the fees in question, and indicated that it would be okay for the trustees to rehire many of those lawyers. Critics contended that the $1 million cost of the “second opinion” was itself a waste of trust resources.

WILL CONSTRUCTION. Mrs. Bishop’s will gives her trustees discretion “to devote a portion of each year’s income to the support and education of orphans, and others in indigent circumstances.” It is tempting to view this as a second charitable mission, one that is separate and apart from the primary mission of running Kamehameha Schools. So viewed, it would support any number and variety of outreach programs. But Hawaii’s Territorial Supreme Court ruled in 1910 that “support and education,” as used in Mrs. Bishop’s will, must be provided at the Kamehameha Schools: “The construction contended for by the [attorney general] that the support and education contemplated was to be furnished elsewhere than at the schools and that support can be furnished independently of education would require undue straining of the language used…. In our opinion the clause under consideration refers to support and education at the Kamehameha Schools only and not to support independently of education.”

Click here to download the pdf or word file version of the Legal Issues